"No podemos sentarnos y

hablar de cómo se parece Nixon a Hitler

porque no puede existir un Hitler

sin un pueblo que lo apoye"

BAJO EL BOMBARDEO

La famosa cantante folklórica y pacifista Joan Báez dio una charla en la Iglesia Memorial de Stanford de Palo Alto (California, Estados Unidos) el 12 de enero de 1973, hablando de su estadía de dos semanas en Hanoi. Viajó en compañía del Brigadier General retirado Telford Taylor, el Rev. Michael Allen y Barry Romo de VVAW con el propósito de entregar más de 600 cartas dirigidas a prisioneros de guerra estadounidenses. La comitiva llegó a Vietnam del Norte el 17 de diciembre. El viaje, que fue auspiciado por el Comité de Enlace, fue interrumpido el segundo día a raíz del bombardeo más intenso que se había registrado en toda la guerra.

Aquí transcribimos parte de la charla dada en Stanford; la cinta magnetofónica original y el registro de las preguntas y respuestas que siguieron luego pueden pedirse al Institute.

BAJO EL BOMBARDEO

Hanoi, diciembre de 1972

Esta última Navidad me hicieron un regalo. Fue el regalo más bello que recibí alguna vez en mi vida, con la excepción de mi hijo. El regalo consistió en la posibilidad de compartir con el pueblo vietnamita una pequeña parte de las agonías que les venimos proporcionando durante los últimos ocho años.

Durante los once días de bombardeo navideño pude gozar del efecto del 60% de nuestros impuestos, que se canalizan hacia un eufemismo conocido con el nombre de “Defense Departmen” (Ministerio de Defensa). Pude obtener una nueva perspectiva sobre el significado de aquel nombre.

Durante los once días que experimenté la vida en Hanoi, las cosas que sentí y vi, pensé y olí me resultaron atroces, aterrorizantes y me partían el alma; me resultaron imposibles de asimilar entonces, y aún hoy sigo sin poder asimilarlas la mayor parte del día y la mayor parte de mis horas de sueño.

Este regalo me ha hecho testigo de esta guerra, y desde ese lugar quiero contarles algunas de las cosas que vi y sentí.

Cuando llegamos a Hanoi se nos llevó a cada uno por separado, a fin de que pudiéramos obtener la mayor información posible. Mantuve una conversación muy interesante con un hombre llamado Quat, el líder del grupo. Le dije que yo era pacifista y que de ninguna manera había viajado a su país a decirle lo que tenía que hacer; por el contrario, había viajado para averiguar, desde su punto de vista, lo que nosotros, los estadounidenses, debíamos hacer mejor. Quat se mostró muy respetuoso durante toda mi estadía en Hanoi en relación a mis opiniones e ideas; nunca me llevó a mí, ni al grupo, a ver un bombardero B-52 derribado para no correr el riesgo de herir nuestro orgullo.

La segunda noche en Hanoi estábamos en una habitación del hotel, mirando una película sobre gases tóxicos, de los que el Defense Department estadounidense afirma que no son tóxicos. Veíamos cómo unos monos echaban espuma por la boca y morían al cabo de doce segundos, y cómo pasaba lo mismo con gatos, cuando de repente escuchamos un ruido. Fue un sonido que me transportó de vuelta al cuarto grado de la escuela primaria, un sonido que ordenaba: “Métete debajo del escrito”. Sin embargo, esta vez no

había escritorio, y no estaba en cuarto grado: era real. (NdT: Se refiere a la sirena que avisa del bombardeo aéreo. Cuando ella asistía a la escuela primaria aprendió, junto con sus compañeras y compañeros, a saltar y esconderse debajo del escritorio de la sala al sonar la alarma.)

Según su costumbre, los vietnamitas nos dijeron: “Ay, disculpen, es un ataque”.

Dije: “¿Disculpar A QUIEN por el ataque?”

©1973 Joan Baez

Under the bombs - Bajo el bombardeo (fragmento)

Publicado por el Institute for the Study of Non-Violence - Instituto para el

Estudio de la No-Violencia

“Vi a una anciana

y al principio me pareció que entonaba una canción de victoria;

algunas veces

una casa es arrasada sin que muera ningún familiar

y hay un gran regocijo.

Me

parecía que cantaba algo alegre mientras alzaba un ladrillo

y lo volvía a poner

en el suelo; levantaba un cascote y hacía lo mismo.

Había zapatos y pedazos de carne a su alrededor

y aunque todo era muy macabro, pensé que su familia

había

sobrevivido en medio de ese horror.

Entonces le vi la cara, la misma cara que

hemos visto

un millón de veces en los afiches que muestran la cara de

agonía

de las víctimas de la guerra;

una agonía imposible de explicar o

describir.

Un intérprete vietnamita traducía para la prensa francesa y dijo:

- Ahora

ella dice:

“¿Dónde estás ahora, hijo mío, dónde estás ahora?”

Lo

repetía una y otra vez.

Me descompuse y entonces Barry me llevó de vuelta al

auto. “

"Si es un caza Phantom vuela por debajo del

radar,

así que no hay posibilidadde que suene la alarma,

de modo que lo que te

despierta

es el estruendo de las bombas".

Joan Baez y su madre arrestadas.

Joan Baez saliendo de la cárcel después de estar meses detenida

Joan Baez: “ C'era un ragazzo che come me

amava i Beatles e i Rolling

Stones” (1967)

“Significa que tenemos que dejar de pagar nuestros

impuestos;

no nos podemos quejar de los bombarderos B-52

y estar pagándolos al mismo tiempo.”

Convocatoria al desarme escrita y diseñada por mí,

impresa y distribuida por

American Friends Service Committee,

1968

Marchando contra la guerra con Donovan

Joan Baez adolescente protestando contra la guerra

Joan Baez y su familia y recortes de

prensa atacándola, 1967

The Boston Globe contra Joan Baez, 1967

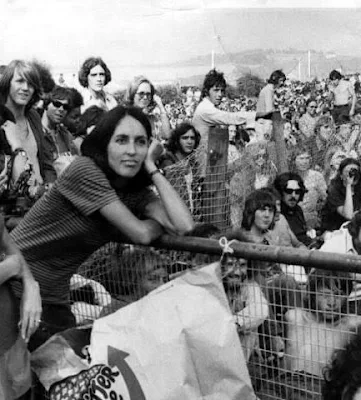

Joan Baez: 1973, después de haber estado en Hanoi

Joan Baez celebrando el fin de la guerra

Carta Abierta a la República Socialista de Vietnam:

denunciando la violación de derechos humanos

del gobierno comunista

Where are you now, my son?

¿Dónde estás ahora, hijo mío?

Words and Music by Joan Baez

Letra y Música Joan Baez

¿Dónde estás ahora, hijo mío?

Words and Music by Joan Baez

Letra y Música Joan Baez

It's walking to the

battleground that always makes me cry

I've met so few folks in my time who weren't afraid to die

But dawn bleeds with the people here and morning skies are red

As young girls load up bicycles with flowers for the dead

I've met so few folks in my time who weren't afraid to die

But dawn bleeds with the people here and morning skies are red

As young girls load up bicycles with flowers for the dead

Caminamos sobre el campo de

batalla que siempre me hace llorar

He conocido tan poca gente

en mi tiempo que no tenga miedo a morir

Pero amanece sangrando con

la gente aquí y los cielos de la mañana son rojos

Como las cargas de las

bicicletas de las muchachas que llevan flores para los muertos.

An aging woman picks along

the craters and the rubble

A piece of cloth, a bit of shoe, a whole lifetime of trouble

A sobbing chant comes from her throat and splits the morning air

The single son she had last night is buried under her

A piece of cloth, a bit of shoe, a whole lifetime of trouble

A sobbing chant comes from her throat and splits the morning air

The single son she had last night is buried under her

They say that the war is

done

Where are you now, my son?

Where are you now, my son?

Una anciana agarra entre los

cráteres y los escombros

Un pedazo de tela, un zapato

destrozado, una vida llena de problemas

Un canto sollozante sale de

su garganta y atraviesa el aire de la mañana.

Su único hijo anoche fue

enterrado bajo ella.

Ellos dicen que la guerra

acabó, entonces

¿Dónde estás ahora, hijo

mío?

An old man with unsteady

gait and beard of ancient white

Bent to the ground with arms outstretched faltering in his plight

I took his hand to steady him, / stood and did not turn

But smiled and wept and bowed and mumbled softly, "Danke shoen"

Bent to the ground with arms outstretched faltering in his plight

I took his hand to steady him, / stood and did not turn

But smiled and wept and bowed and mumbled softly, "Danke shoen"

Un anciano con paso

inestable y barba blanca de la antigua

Bent caminaba con los brazos

extendidos, vacilando en su difícil situación

Tomé su mano para ayudarlo

antes de que cayera, él no se volteó para mirarme

Pero sonrió y lloró y se

inclinó y murmuró suavemente “Danke shoen”

(Gracias en alemán)

The children on the

roadsides of the villages and towns

Would stand around us laughing as we stood like giant clowns

The mourning bands told whom they'd lost by last night's phantom messenger

And they spoke their only words in English, "Johnson, Nixon, Kissinger"

Would stand around us laughing as we stood like giant clowns

The mourning bands told whom they'd lost by last night's phantom messenger

And they spoke their only words in English, "Johnson, Nixon, Kissinger"

Now that the war's being won

Where are you now, my son?

Where are you now, my son?

Los niños al borde de la

carretera de los pueblos y ciudades

Están de pie alrededor de

nosotros riendo como si fuéramos payasos gigantes

Las noticias de la

mañana les dicen a quién ellos perdieron anoche por culpa del

mensajero fantasma

y dicen las únicas palabras

que saben en inglés, " Johnson, Nixon, Kissinger "

Ahora que la guerra se

ganó

¿Dónde estás ahora, hijo

mío?

The siren gives a running

break to those who live in town

Take the children and the blankets to the concrete underground

Sometimes we'd sing and joke and paint bright pictures on the wall

And wonder if we would die well and if we'd loved at all

Take the children and the blankets to the concrete underground

Sometimes we'd sing and joke and paint bright pictures on the wall

And wonder if we would die well and if we'd loved at all

La sirena suena y la gente

de la ciudad corre

Llevan sus niños y sus

mantas a los refugios antiaéreos

A veces nosotros cantamos y

reímos y pintamos cuadros brillantes en la pared

Y que maravilla sería si

nosotros pudiéramos morir bien y amando todo.

The helmetless defiant ones

sit on the curb and stare

At tracers flashing through the sky and planes bursting in air

But way out in the villages no warning comes before a blast

That means a sleeping child will never make it to the door

At tracers flashing through the sky and planes bursting in air

But way out in the villages no warning comes before a blast

That means a sleeping child will never make it to the door

The days of our youth were

fun

Where are you now, my son?

Where are you now, my son?

Personas sin cascos se

sienta desafiantes en la acera y miran fijamente

Sin parpadear al cielo y los

aviones hacen estallar al aire

Pero en la salida de los

pueblos no hay ninguna alarma de bombardeo

Eso significa que un niño

dormido nunca llegará a la puerta

Los días de nuestra juventud

eran divertidos

¿Dónde estás ahora, hijo mío?

From the distant cabins in the sky where no man hears the sound

Of death on earth from his own bombs, six pilots were shot down

Next day six hulking bandaged men were dazzled by a room

Of newsmen. Sally keep the faith, let's hope this war ends soon

¿Dónde estás ahora, hijo mío?

From the distant cabins in the sky where no man hears the sound

Of death on earth from his own bombs, six pilots were shot down

Next day six hulking bandaged men were dazzled by a room

Of newsmen. Sally keep the faith, let's hope this war ends soon

Desde cabinas distantes en el cielo, donde no escuchan el sonido

De la muerte en la tierra de sus propias bombas, seis pilotos fueron derribados

Al día siguiente seis descomunales hombres vendados fueron deslumbrados por una sala de periodistas. Sally mantiene la fe, la esperanza de que la guerra termine pronto

In a damaged prison camp where they no longer had command

They shook their heads, what irony, we thought peace was at hand

The preacher read a Christmas prayer and the men kneeled on the ground

Then sheepishly asked me to sing "They Drove Old Dixie Down"

Yours was the righteous gun

Where are you now, my son?

En un campo de prisioneros dañado donde no había nadie al mando,

Meneando la cabeza, qué ironía, pensamos que la paz estaba a la mano

El cura leyó una oración de Navidad y los hombres se arrodillaron en el suelo

Luego tímidamente me pidieron que cantara "They Drove Old Dixie Down"

Tu arma era justa

¿Dónde estás ahora, mi hijo?

We gathered in the lobby celebrating Chrismas Eve

The French, the Poles, the Indians, Cubans and Vietnamese

The tiny tree our host had fixed sweetened familiar psalms

But the most sacred of Christmas prayers was shattered by the bombs

So back into the shelter

where two lovely women rose

And with a brilliance and a fierceness and a gentleness which froze

The rest of us to silence as their voices soared with joy

Outshining every bomb that fell that night upon Hanoi

And with a brilliance and a fierceness and a gentleness which froze

The rest of us to silence as their voices soared with joy

Outshining every bomb that fell that night upon Hanoi

With bravery we have sun

But where are you now, my son?

Nos reunimos en el lobby celebrando Navidad Eva

Los franceses, los polacos, los indios, los cubanos y vietnamitas

El pequeño árbol de nuestro anfitrión tenía dulces y familiares salmos

Pero la más sagrada de las oraciones de Navidad fue destrozada por las bombas

Así que de nuevo al refugio,

donde dos mujeres encantadoras de rosa

y con un esplendor y una

fiereza y una suavidad que nos congeló

nos quedamos en silencio

escuchando cómo sus voces se elevaban con alegría

Para eclipsar cada bomba que cayó esa noche en Hanoi

Para eclipsar cada bomba que cayó esa noche en Hanoi

Con la valentía tenemos el

sol

Pero, ¿dónde estás ahora, mi hijo?

Pero, ¿dónde estás ahora, mi hijo?

Oh people of the shelters what a gift you've given me

To smile at me and quietly let me share your agony

And I can only bow in utter humbleness and ask

Forgiveness and forgiveness for the things we've brought to pass

Oh gente de los refugios que regalo me han dado

Sonreírme y tranquilamente dejarme compartir su agonía

Y sólo puedo inclinarme en absoluta humildad y pedirles

perdón y perdón por las cosas que les hemos hecho pasar

The black pyjama'd culture that we tried to kill with pellet holes

And rows of tiny coffins we've paid for with our souls

Have built a spirit seldom seen in women and in men

And the white flower of Bac Mai will surely blossom once again

I've heard that the war is done

Then where are you now, my son?

La cultura del piyama negro que nosotros tratamos de matar con agujeros de pellet

E hileras de pequeños ataúdes, nosotros los hemos pagado con nuestras almas

Ustedes tienen un espíritu que rara vez vi en mujeres y en hombres

Y la flor blanca de Bac Mai seguramente florecerá una vez más

He escuchado que la Guerra acabó,

Entonces, dónde estás ahora,

hijo mío?

© 1973 Joan Baez

Joan Baez y su madre

Joan Baez en Camboya, 1980, llevando alimentos y medicinas

Joan Baez regresa a Vietnam 41 años después de su histórica visita en las navidades de 1972/Joan Baez returns to past in Vietnam, interview by Chris Brummit, AP, Apr. 10, 2013

|

| Joan Baez apoyada en la pared del histórico bunker del Metropole Hotel en Hanoi, donde se refugió en diciembre de 1972 de los bombardeos americanos B-52. In this March 31, 2013 photo released by Metropole Hanoi, Joan Baez stands with her back to the wall of an historic bomb shelter under the Metropole Hotel in Hanoi, Vietnam. The folk singer and social activist spent a few days recently reliving her past, returning to Hanoi for the first time since December 1972, when American B-52s were raining bombs on it. (AP Photo/Metropole Hanoi) |

Joan Baez, la cantante estadounidense de folk ha vuelto a Vietnam, a Hanoi. A la ciudad a la que viajó hace 40 años en una misión de paz y al lugar en el que se resguardó por culpa de la guerra, un búnquer al que ha dedicado uno de sus lamentos.

“Fue la primera vez en que me enfrentaba a la muerte, a la mortalidad, fue terrible desde una perspectiva cósmica. Sabes que todo el mundo acaba muriendo pero siempre piensas que no te va a tocar a ti. El hecho de que haya estado tan cerca de morir tantas veces me ha cambiado”, decía Baez.

La cantante de 72 años fue, en los finales de los sesenta, una ferviente activista contra la guerra de Vietnam. Un conflicto que moldeó su personalidad y que siempre estará en su memoria y en las canciones que estremecieron a toda una generación.

Fuente: Euronews

|

| In this April 6, 2013 photo, Joan Baez laughs while speaking to former staff at the Metropole Hanoi in Hanoi, Vietnam. The folk singer and social activist visited Vietnam recently for the first time since she came to the country in December 1972 as part of an American peace delegation. (AP Photo/Dinh Hau) Joan Baez ríe mientras escucha al personal del Hotel Metropole Hanoi en Hanoi, en su regreso a Vietnamdesde Diciembre de 1972. |

Joan Baez returns to past in Vietnam,

interview by Chris Brummit, Apr. 10, 2013

|

| In this April 5, 2013 photo, Joan Baez speaks to a reporter in her hotel room in Hanoi, Vietnam. The folk singer and socialactivist visited Vietnam recently for the first time since she came to the country in December 1972 as part of an American peace delegation. Baez painted the picture of the young boy during her recent stay in Hanoi. (AP Photo/Dinh Hau) Joan Baez en la habitación de su hotel hablando con el periodista. La cantantey pacifista volvió a Vietnam por primera vez desde diciembre de 1972, cuando viajó como parte de una delegación americana por la paz. |

HANOI, Vietnam (AP) — At 72, Joan Baez is not short of events to anticipate: She has her mother's 100th birthday party, a tour of Australia and a new passion — painting — to explore. But the folk singer and social activist has spent a few days reliving her past, returning to Hanoi for the first time since December 1972, when American B-52s were raining bombs on it.

Each night, Baez would scurry to the bunker underneath her government-run hotel, her peace mission to North Vietnam interrupted by the reality of war. With the blast waves making her night dress billow, she would tremble until dawn, sometimes singing, sometimes praying.

"That was my first experience in dealing with my own mortality, which I thought was a terrible cosmic arrangement," Baez said last week in an interview in the same hotel in the Vietnamese capital, taking a break from a painting-in-progress on an easel beside her. "It is OK for everyone else to die, but surely there was another plan for me?" she joked.

The U.S. launched its heaviest bombing raids since World War II against targets in Communist North Vietnam, which was fighting to overthrow the U.S.-backed government of South Vietnam. The bombardment, which mostly targeted Hanoi, lasted 11 days over Christmas in 1972.

Baez traveled to Vietnam then with three other Americans to see firsthand the effects of the war and deliver mail to U.S. prisoners being held in Hanoi. Many at home were angry at her trip because they believed it gave support to America's enemy. After the war, Baez spoke outagainst human rights abuses by the victorious Communist government.

Baez stayed this time in the same hotel where she and the rest of the peace delegation were put up 40 years ago by the North Vietnamese government, which was happy to welcome those willing to listen to its side of the story. The building is now more luxurious, and goes under a different name, The Metropole Hanoi, but much of it remains the same.

She was quick to visit the recently unearthed bunker that sits just beyond one of the hotel bars. Soon after descending, she put her hand to the cement wall, closed her eyes and sang out the African-American spiritual, "Oh Freedom," a song she often sang during civil rights rallies in the United States in the 1960s.

"I felt this huge warmth," she said of her feelings. "It was gratitude. I thought I would feel all these wretched things about a bunker but it was love that it took care of me."

On her return from Vietnam in 1973, she released an experimental album, "Where Are You Now, My Son?" The record features taped, spoken-word recordings taken from the bunker and the hotel and the sounds of Hanoi, including air-raid sirens and dropping bombs. Over a piano accompaniment, Baez sings of her time in Hanoi, including the Christmas celebrations in the hotel lobby and morning trips to see the devastation left by the American bombs.

Baez's time trip to Vietnam is just one part of a life that blazes through the cultural and political history of the United States.

She began her musical career in the folk clubs of Cambridge, where in 1961 she met Bob Dylan, who at that time was little known while she was a rising folk star. They had a high-profile romantic and musical relationship for a few years. Known mostly for singing other people's songs, she has recorded more than 50 albums, mostly recently a 2008 record that was produced by Steve Earle.

Baez has always placed her social activism ahead of her musical career, a commitment in part fostered by parents' conversion to Quakerism when she was a child. A pacifist, she was a leading voice in the civil rights movement and the anti-Vietnam War protest. She has supported scores of campaigns across the United States dealing with poverty, racism, environmental degradation and the wars in Iraq, as well as oversea causes.

She was on a private trip to Vietnam this time but visited a local international school where she sang and spoke to the children. She reminded them of her first act of civil disobedience as a 16-year-old when she refused to go home during an air-raid drill from her school in California. Asked how she keeps going as an activist, she spoke of the importance of personal "little victories" to set against the inevitable "big defeats" such as climate change and the unchecked pace of arms sales around the world, but also spoke of her need now to stay at home with her mother.

Baez had always shunned party politics, but in 2008 made an exception for Barack Obama. One year into his second term as U.S. president, she now says she is unlikely to do so again. "In some ways I'm disappointed, but in some ways it was silly to expect more," she said. "If he had taken his brilliance, his eloquence, his toughness and not run for office he could have led a movement. Once he got in the Oval Office he couldn't do anything."

To a question on the limits of her pacifism — or as she says "the what-if-someone-is-going-to-shoot-your-grandma" scenario — she replies:

"Anybody who says they would never do this in any situation would probably have to check themselves, but for the way I lived my life and the way I plan to live my life does not include violence," she said. "The longer you practice nonviolence and the meditative qualities of it that you will need, the more likely you are to do something intelligent in any situation."

"Anybody who says they would never do this in any situation would probably have to check themselves, but for the way I lived my life and the way I plan to live my life does not include violence," she said. "The longer you practice nonviolence and the meditative qualities of it that you will need, the more likely you are to do something intelligent in any situation."

She said America should have not responded with violence after the 9/11 attacks.

"People say if 'we have tried everything' but they haven't really tried anything, because they really want to clobber (something)," she said. "It is what we know, it is what is familiar — revenge and that stuff."

Baez still tours the globe, but is now slowing down — just two monthlong tours this year compared to her previous three.

But it's painting now that really fires her. She has been at it for just eight months. The acrylic in the hotel in Hanoi of a young Vietnamese boy against an orange background is her first work that has ever been framed.

"I have literally switched my interest in music to painting, which is convenient because it's been 53 years and it's not that easy to sing now," she said. "People wouldn't know it, but the voice goes down and there is huge pressure to keep it up and it means a lot more vocalizing and a lot more concentration. I'm really ready to move on."

Baez got in contact with the hotel after seeing media reports of the bunker being unearthed. She gave friends of hers visiting Hanoi in December a signed copy of "Where Are You Now, My Son?" with the instructions they should give it to the hotel management if "they are the right people" and, if they weren't, to bring it home again.

They handed it over to Metropole general manger Kai Speth, who led the hunt for the shelter and is proud of the hotel's history. He gave Baez's friends a book about the hotel with a note to Baez saying he would love to welcome her back. In February, she emailed saying she would like to come. Less than two months later she was walking through the door.

"I don't believe in coincidences," said Baez. "Something in me was ready to come back and apparently hadn't been up until now."

On the Saturday before her flight left, Baez shared tales of life of Hanoi under American attack and the hotel's history with former staff, including its hairdresser and general manager. Many of them were on double duty: digging graves for the victims of the bombing as well as serving the hotel guests.

The ex-general manager gave her an embroidered bag, which she said she would use to carry the soaps she planned to steal from the hotel. Housekeeper Tieu Phuong said she remembered Baez staying at the hotel. She also remembered seeing some American pilots, who were released from Hanoi jail at the end of the war, staying at the hotel before flying home and thinking "they looked so nice, how could they bomb our country?"

Under the hazy spring sun, Baez took her hand and tried to explain: "It's so true; they were just kids, they were just following orders."

Fuente: AP

Abril 2013

Follow Chris Brummitt on Twitter at twitter.com/cjbrummitt